Uncovering Nazi massacre of Jews on Belarus building site — BBC News, April 1, 2019

By Sarah Rainsford

BBC News, Brest, Belarus

1 April 2019

Original link

The stories of Brest’s Jewish community

Slowly, gently even, young soldiers scrape away the dirt of decades from human bones. Tangled with the remains are shreds of cloth and the soles of shoes.

They’re uncovering a little-known chapter of the Holocaust on a construction site in western Belarus.

The mass grave was discovered as building work began on an elite apartment block.

Since then, specially trained soldiers have unearthed the remains of more than 1,000 Jews, killed when the city of Brest was occupied by Nazi Germany.

Human remains were found as construction workers dug foundations for a new apartment block

“There are clear bullet holes in the skulls,” says Dmitry Kaminsky.

His military team usually searches for the bones of Soviet soldiers. Here they have removed the small skulls of teenagers instead, and a female skeleton with the remains of a baby, as if she’d been cradling it.

Before World War Two, almost half the 50,000-strong population of Brest were Jews.

Up to 5,000 men were executed shortly after the German invasion in June 1941.

Those left were later crammed into a ghetto: several blocks of the city centre surrounded by barbed wire.

In October 1942, the order came to wipe them out.

This was the forest at Bronnaya Gora where the remaining Jews of Brest were taken and murdered

This was the forest at Bronnaya Gora where the remaining Jews of Brest were taken and murdered

They were herded on to freight trains and driven over 100km (62 miles) to a forest.

At Bronnaya Gora, thousands were led to the edge of a vast pit and shot.

It’s thought the grave discovered within the old ghetto includes those who managed to hide at first, only to be rooted out.

“When my parents returned, the city was half empty,” Mikhail Kaplan says, flicking through black and white snapshots at his kitchen table.

Mikhail looks out over the site of the mass grave in Brest’s old wartime ghetto

His mother and father only escaped the massacre because they were away when the Germans overran Brest. Mikhail’s photographs are of aunts, uncles and cousins who were all killed.

“My father never spoke about what happened, it was too painful. But my grandmother cried all the time remembering Lizochka, Lizochka,” he recalls, reaching for a photograph picture of his Aunt Liza dressed up for a night out with friends.

Mikhail’s aunt Liza (R) is seen going out with two friends – all three were murdered by the Nazis

Mikhail’s aunt Liza (R) is seen going out with two friends – all three were murdered by the Nazis

Here Liza poses with her daughter Ruth, who also died

Here Liza poses with her daughter Ruth, who also died

After the war, though, Mikhail says the Jewish massacre was not commemorated.

“Everyone knew what had happened, but no-one spoke of it officially,” he says. “The Germans destroyed us, deliberately. The Soviets just stayed silent.”

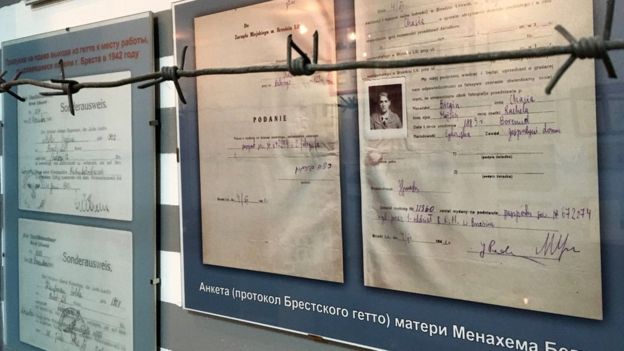

Even now, the only Holocaust museum in Brest is a room in a basement, curated and run by the small Jewish community that settled in the city after its liberation.

The displays include the miracle stories of the handful of ghetto survivors who hid beneath false floors or behind walls in their houses for months.

The small Jewish museum in Brest describes life in the ghetto

The small Jewish museum in Brest describes life in the ghetto

There’s also a city register kept by the Germans. On 15 October 1942 it records 17,893 Jews in Brest. The next day, that figure is scratched out.

“That’s how we know when the ghetto was liquidated,” community leader Efim Basin explains.

He had suspected that workers would find some bodies at the construction site, but never so many.

“This only underlines how little we know about our history,” he adds.

Efim has been exploring the archives over the years, working to correct that. But witness testimonies are limited. And the fate of the Jews in Belarus has always been merged with the catastrophic losses suffered overall under occupation.

Gravestones from the Jewish cemetery were cleared away to make for a sports stadium

Gravestones from the Jewish cemetery were cleared away to make for a sports stadium

“Officials would repeat the mantra ‘Never forget!’ about the dead, but the Jewish part was hushed up,” Efim recalls. “War memorials were all dedicated to ‘Soviet citizens’,” he says, calling that part anti-Semitism, part the Soviet stress on “one nation”.

“But that was very offensive. The Jews were not killed for resisting the Nazis. They were killed because they were Jews.”

Touring the city on foot, Efim points out the many traces of Jewish life at its heart.

Brest’s cinema was built on top of the town’s main synagogue during the Soviet era

Brest’s cinema was built on top of the town’s main synagogue during the Soviet era

They include the main synagogue, with a cylindrical cinema built on top of it in the Soviet years. The original marble walls are still intact inside, too solid to destroy.

The Jewish cemetery, partly demolished by the Nazis, was then finished off by the USSR. The graves were heaped with soil and a sports stadium was installed on top.

The only Holocaust memorial in the city centre was put up by the Jewish community itself and the diaspora.

Brest’s memorial to the thousands of Jewish victims of the Holocaust from the city was erected by its surviving community

Brest’s memorial to the thousands of Jewish victims of the Holocaust from the city was erected by its surviving community

So they’re pushing for a new, official monument now at the execution site. The proposals so far, though, include planting some trees in what will eventually become the garden of the luxury flats.

“Some people say they’re building on bones, but that isn’t true,” Alla Kondak, of the city’s culture department insists. “We will only stop [excavation] work once all the remains have been recovered.”Those bones will be reinterred at the city cemetery, along with soil from the site, and Ms Kondak sees no need for more.

“There are graves everywhere here! The Germans shot and buried people on the spot,” she argues.

The mass grave was found in an area of the old Brest ghetto where the Nazis forced the city’s Jewish population to live

The mass grave was found in an area of the old Brest ghetto where the Nazis forced the city’s Jewish population to live

But it seems few locals are aware of the specific fate of the Jews.

“We didn’t learn anything at school about the Brest ghetto,” two women in their twenties admit sheepishly. “I don’t think anyone our age really knows.”

“I know nothing about the ghetto or the grave,” an older lady says, close to the excavation site, and hurries on.

But as another day’s digging there draws to a close, the soldiers emerge from the pit balancing more muddy crates full of bones.

It’s a history that becomes harder to ignore, with every fragment recovered from the ground.