Ghetto on the Territoty of Polotsk in the Years of Occupation (1941 – 1944)

Polotsk was occupied by the German army on July 15th, 1941. In accordance with administrative-territorial separation, Polotsk was included into the home front zone of the group of armies “Center” and remained a part of it until July 4th, 1944.

The city had its own commandant’s office, which was located in two-storey brick houses to the left side of the Western Dvina River. That was where the police, gendarmerie and hostel were established. The police had a criminal and passport department. The local commandant’s office was located in a two-story building at the junction of Leninskaya and Ordzhonikidze Streets.

From the very first days of occupation there were activities to restrict the rights of the Jewish population living on the territory of Polotsk. According to a decree, which was issued on July 7th, 1941, “all the Jews living on the occupied Russian territory, those who have reached the age of 10, are to wear a white stripe with the Star of David, or a yellow 10-centimeter stripe on the right sleeve of their clothes…It is forbidden to greet Jews.” Violators were punished. According to another resolution, dated February 24, 1942, Jews were prohibited to be accepted into hospitals or outpatient clinics. Jewish doctors were allowed only to treat Jewish patients.

Jews were strictly forbidden to change residence without official permission; they were not allowed to walk on the sidewalks, visit theatres, cinemas, libraries, museums or any schools. They were not allowed to sell anything.

The next step was separation of the Jewish population from the rest of the local population in a ghetto.

The ghetto on the territory of Polotsk was established within 2-3 days after the occupation of the city. All the Jews had to move to Kommunisticheskaya, Gogolevskaya, Voikova, Internatsionalnaya (former Jewish) Streets, while all the Russian and Belorussian residents were driven out of there into the empty Jewish apartments.

There was an outpatient clinic, a bathhouse and a laundry, a power station, a school, a synagogue and a post office on the territory of the ghetto. Many buildings in the ghetto were demolished. The ghetto was surrounded with barbed wire but not guarded. About ten families lived in each house; all in all there were about 5,000 people. The Jewish population of Polotsk before the war constituted 10-12 thousand people, which accounted for about half of the total population.

Interior self-government was performed by “Judenrats”, appointed by the Nazis for collection of fees and duties, organization of workforce and epidemic prevention, as well as for distribution of food.

In the ghetto in Polotsk the Judenrat was headed by Abram Sherman, a former carpenter. His assistant was Apkin, a former employee of bicycle repair shop. They were ordered by Germans to select people for work, which, they hoped, would save their lives. However, A. Sherman was shot before everyone else.

In September, 1941, the ghetto was moved to the outskirts of Polotsk, the village of Lozovka. About 8,000 people were located here, including the Jews from neighboring villages. They were all living in 10 barracks at a brick factory. The ghetto was surrounded with a fence with barbed wire and guarded by policemen. The Germans came here only to rob. They would order everyone to go outside and then search the barracks for valuables.

They would also tear away rings and watches right from the people’s hands. Some, especially women, were forced to get undressed and then were searched.

Each barracks had about 40-50 people. Very often the residents died of starvation and illnesses.

They were given food once a day, which was unsalted flour and 100 grams of bread. Witnesses said: “Even though Russians were not allowed to enter the ghetto, housemaid Lena brought milk. She was caught and taken to the commandant’s office. They threatened her, took her cow but finally let her go.” The ghetto residents were not given any water. Some of them were lucky to have a chance to leave the ghetto through a hole in the fence. They would exchange money and valuables for food and bring it to the ghetto. They had to get food somewhere else, because 100 grams of bread per day was not enough food. The people who were unable to work were shot or severely beaten up. Every day the ghetto gates would open and a column of people made up of thousands of people would be sent to work. They were sent to do the dirtiest, hardest and frequently physically impossible work. They slept outside in the mud. The Nazis treated Jews worse than livestock. They did not feel pity for anyone, killing children right in their mothers’ arms. Such life conditions lead to complete exhaustion. Those who did not work were not given anything. They were left with one thing – death.

The people died in huge numbers of starvation, the cold and illnesses. O. Baltrukova, a Polotsk resident, witnessed: “Right in front of my eyes more than 500 bodies were taken out of the camp and buried in the Starosvetskoye cemetery.”

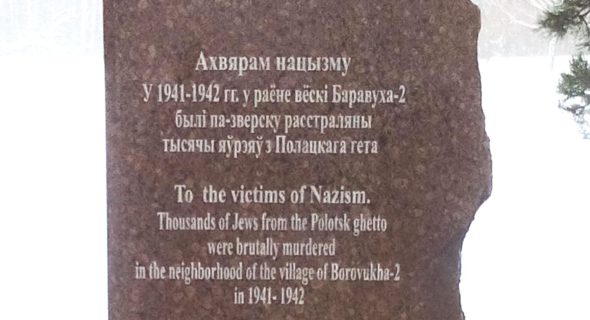

It was possible to flee from the ghetto, but the people did not know where to go. There were rumors about the people who had been taken from Polotsk in cars at the beginning of the occupation: some said they had been seen gathering crops somewhere, some said they had been sent to Palestine. In the morning of November 21st the Nazis and policemen arrived at the ghetto again. The residents assumed they again were there to rob them. Everyone was ordered to leave the barracks and form a column. Then they were told to walk towards Borovuha-2, which was 2-3 kilometers away from Lozovka. They did not even guess they were taken to be executed. Someone even had told them they would be sent to Palestine.

The column was several kilometers in length. The people walking in the middle of the column heard shots and realized where they were being taken. An eyewitness remembers: “The column was only guarded by policemen and it was possible to escape. An acquaintance of mine, Pasternak, convinced me to escape but my mother was holding me by the hand and said: “If you run you will be killed anyway. This way we will at least be lying together.” Soon we saw 5-6 ditches across the road from the Russian cemetery. We saw cars, Germans, policemen and piles of clothes… Then I saw everything. The policemen were undressing the people and threw their clothes into the piles. Then the Jews were made to walk towards a ditch. At that moment I managed to break myself loose from the mother’s hand. I was among the people who were taken towards the ditch, but did not actually walk together with them. Some people tried to escape but were shot. There were five Nazis shooting by each ditch. Policeman Shastidko, who used to live in our street, noticed I did not approach the ditch. He shouted at me: “Why are you standing? Come on!” – he hit me on the head with a bicycle chain. The hat I was wearing softened the stroke. I started walking without understanding what I was doing. I heard people shouting and shooting. I ran naked until I reached Kosaverskaya hospital.”

Another witness, resident of the Polotsk ghetto M. Minkovich, narrates: “On November 21 all the ghetto residents were taken to Borovuha-2, where 4 big ditches had been previously made. There were about 15 Germans and 40 policemen, among them Shastidko, Nikolai Oguretsky, Labetsky, Ovlasenko, Sergey Lubelsky, Vasily Pravilo. Everyone was undressed before the execution. Vasily Pravilo was the one who undressed me and before lashed me on the head… However, I happened to survive. After the 21 of November I hid myself in the forest, later – in neighboring villages. Then, from April 12, 1942 to July 3, 1944 I was in Prudnikov’s partisan detachment.”

Witness Z.F. Spiridonova claims that she saw Germans shoot the Jewish population of Polotsk in 1941. The Nazis forced the Jews to dig graves for themselves, then made them lie down and shot. One boy ran off from the ditch and clang to a tree. Then the Germans chopped his arms off.

It can be stated that more than 7000 Jewish residents were executed in the Polotsk ghetto. The executions took place next to the village of Lozovka near a railway crossing. As a rule, children were thrown into the ditches while still alive and buried without being shot.

Daria Kipiatkova,

3rd year student at Polotsk State University.

The research participated in the 2nd Republican contest “Holocaust. History and present time. Tolerance lessons.”

The research original is in archive of the Museum of history and culture of Belarusian Jews.